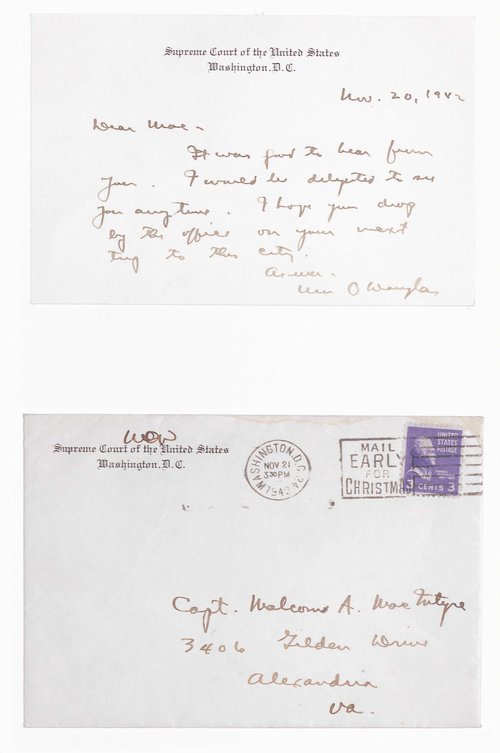

Personal correspondence from Justice William O. Douglas and Malcom A. MacIntyre, 1942

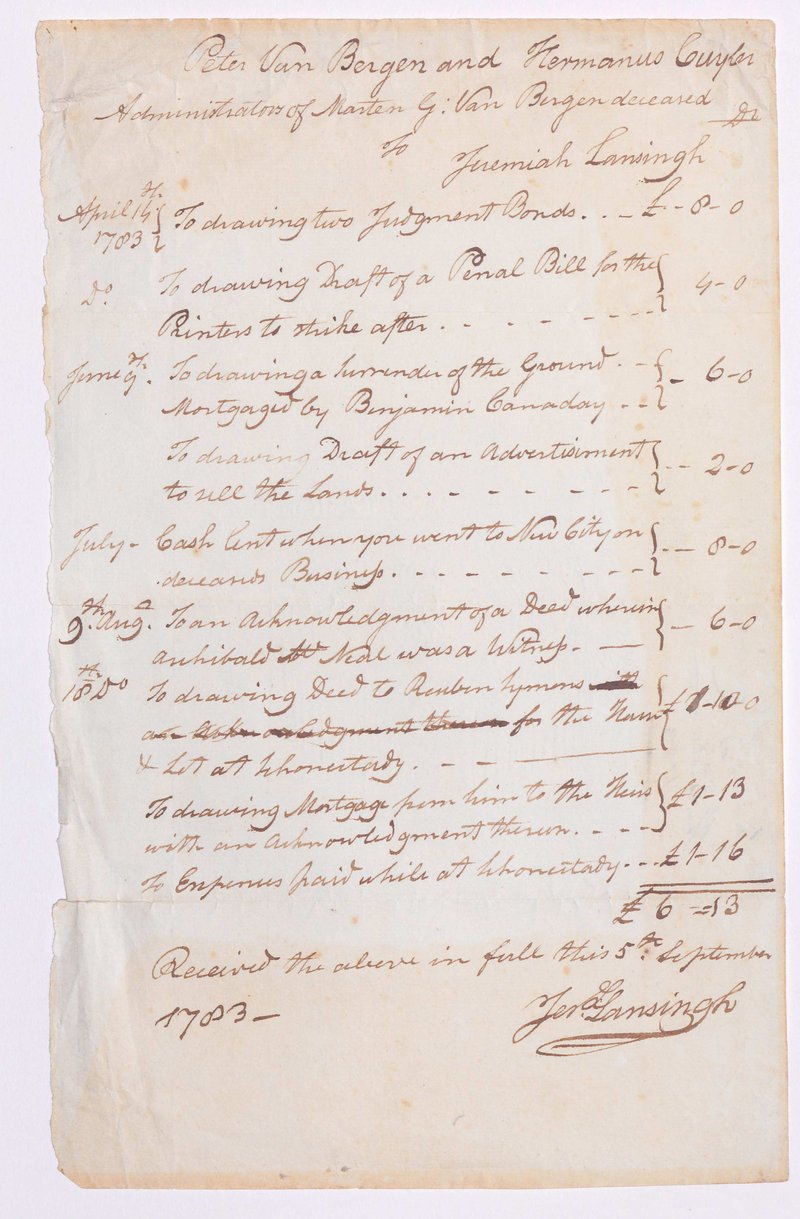

Receipt for Legal Services, Signed. Schenectady County, NY, September 5, 1783. An accounting of legal fees owed to Jeremiah Lansing by Peter Van Bergen and Hermanus Cuyler, administrators of the estate of Martin G. Van Bergen, for such services as "drawing the draft of a penal bill for the printers to strike after" and "drawing two judgement bonds." Van Bergen, Cuyler and Lansing were prominent citizens of Schenectady County, New York.

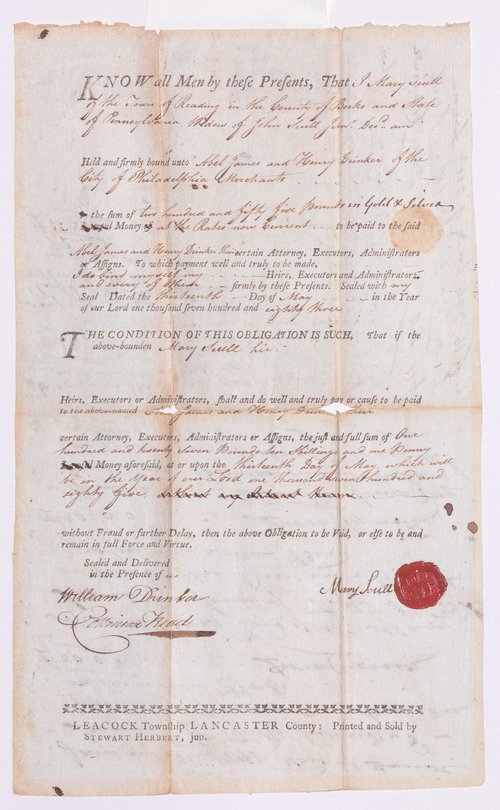

Page 1 of Mortgage Indenture, Signed by Mary Scull, Witnessed by William Drinker and Collinson Read. Reading Township, Berks County, PA, May 30, 1783. An early example of a "home equity loan," Scull, a widow, used the value of her house to borrow 250 pounds "in gold and silver" from Philadelphia merchants Abel James and Henry Drinker. Collinson Read and William Drinker, the witnesses, were prominent Pennsylvania lawyers.

Page 1 of Bail Bond Issued to Nehemiah Allen. New York, August 21, 1798. Allen was placed under a $10.00 bond ''at the suit of John Dodge of a plea of trespass assault and battery.'' According to the docket on the verso, Allen paid his bail on January 14th, 1799 .

Page 2 of Bail Bond Issued to Nehemiah Allen. New York, August 21, 1798. Allen was placed under a $10.00 bond ''at the suit of John Dodge of a plea of trespass assault and battery.'' According to the docket on the verso, Allen paid his bail on January 14th, 1799 .

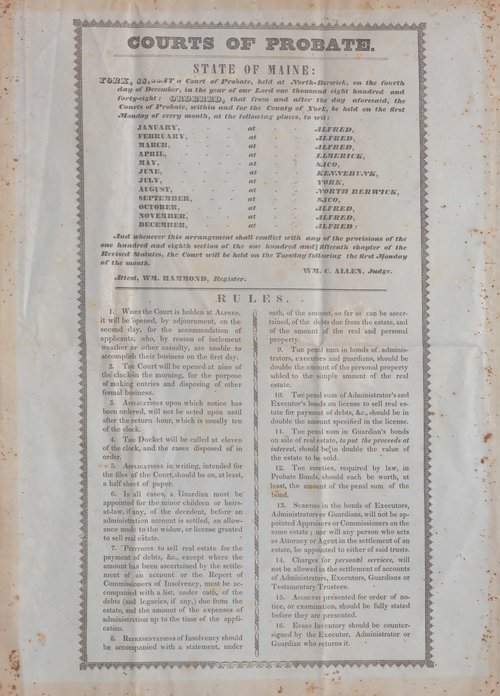

Courts of Probate. State of Maine: York, SS-At a Court of Probate, Held at North-Berwick, On the Fourth Day of December, In the Year of Our Lord One Thousand Eight Hundred and Forty-Eight: Ordered, That from and After the Day Aforesaid, The Courts of Probate, Within and for the County of York, Be Held on the First Monday of Every Month, At the Following Places...[York County, ME, 1871]. This broadside is divided into two sections. The upper section of this broadside outlines the court schedule and locations (Alfred, Limerick, Saco, Kennebunk, North Berwick and York). The lower section is a list of 16 court rules, most of them procedural. Early signature (of a town clerk?) to verso.

15-1/2" x 11" broadside, text within typographical border. Light browning, two vertical and one horizontal fold lines, some dampspotting to margins

Personal correspondence from Justice William O. Douglas and Malcom A. MacIntyre, 1942

Nov. 20, 1942

Dear Mac,

It was good to hear from you. I would be delighted to see you anytime. I hope you drop by the office on your next visit to the city.

As ever,

W. O. Douglas

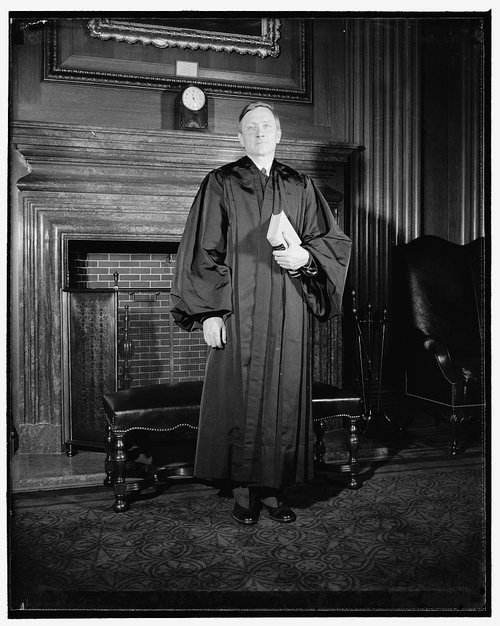

A brief 1942 message between Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States William O. Douglas and a colleague. A former Yale Law School professor and chairman of the Security Exchange Commission, Douglas was confirmed to the Court in 1939. Leading the Court on progressive issues, he remained in office until 1975, making him the longest serving Justice in Supreme Court history.

The letter’s recipient Malcom A. Macintyre was a graduate of Yale Law School and future Under-Secretary of the United States Air Force. Macintyre was later inducted into the Lacrosse Hall of Fame for his sports career in the US and England. His personal papers are archived at the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum.

M. Margaret McKeown. Citizen Justice: The Environmental Legacy of William O. Douglas-Public Advocate and Conservation Champion. University of Nebraska Press, 2022: https://pitt.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01PITT_INST/g3767l/alma99101601498306236

Malcom A. Macintyre, National Lacrosse Hall of Fame, https://www.usalacrosse.com/player-profile/malcolm-macintyre

Finding Aid, Malcom A. Macintyre Papers, https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/research/finding-aids/macintyre-malcolm

Images

Wikimedia, William O. Douglass, April 17, 1939: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/86/William_O._Douglas.jpg

An accounting of legal fees owed to Jeremiah Lansing by Peter Van Gergen and Hermanus Cuyler, administrators of the estate of Martin G. Van Bergen, for such services as “drawing the draft of a penal bill for the printers to strike after” and “drawing two judgement bonds.” Van Bergen, Cuyler, and Lansing were prominent citizens of Schenectady County, New York.

An early example of a “home equity loan.” Mary Scull, a widow, used the value of her house to borrow 250 pounds “in gold and silver” from Philadelphia merchants Abel James and Henry Drinker. This transaction was signed by two witnesses, Collinson Read and William Drinker, prominent Pennsylvania lawyers.

Monetary values are expressed in Pounds Sterling throughout this document, the £ symbol can be seen on the verso. When this document was initially signed on May 30, 1783, the newly independent United States had not yet begun to issue its own currency. The Articles of Confederation introduced in 1777 states that “The United States Congress shall never coin money, nor regulate the value thereof, unless nine states assent to the same.” This created an environment where multiple regional and foreign currencies were circulating in the United States at the same time. This began to change when the United States Constitution was ratified in 1788, giving Congress sole authority to introduce an American system of currency. Section 8 of the Constitution states, “The Congress shall have the power to coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures.” This Constitutional power was expressed four years later in the Coinage Act of 1792, which introduced the dollar as a standard unit of American currency.

Section 20. And be it further enacted, That the money of account of the United States shall be expressed in dollars and that all accounts in public offices and all proceedings in the courts of the United States shall be kept and had in conformity to this regulation.

Despite these regulations, dollars remained rare for many years while the US Mint established operations. It was not until the Coinage Act of 1853 that foreign currency was banned for use in the United States:

Section 3. And be it further enacted, that all former acts authorizing the currency of foreign gold or silver coins, and declaring the same a legal tender in payment for debts, are hereby repealed.

United States National Archives, Articles of Confederation, November 15. 1777, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/articles-of-confederation

United States Mint, Coinage Act of April 2, 1792, https://www.usmint.gov/learn/history/historical-documents/coinage-act-of-april-2-1792

United States National Archives, The Constitution of the United States: A Transcription, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution-transcript

Statutes at Large, Feb. 21, 1857, An Act relating to Foreign Coins and to the Coinage of Cents at the Mint of the United States, https://maint.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/34th-congress/session-3/c34s3ch56.pdf

This bail statement originates from the New York City Mayor’s Court in 1798. Described by the Historical Society of the New York Courts as:

This bail statement originates from the New York City Mayor’s Court in 1798. Described by the Historical Society of the New York Courts as:

“a civil court with jurisdiction limited to the City of New York. In 1691, the court’s jurisdiction was extended throughout the State and the court was continued under the Constitution of 1777. Under the Constitution of 1846, the court’s jurisdiction was again restricted to the City of New York and it was given appellate jurisdiction from orders of the Marine Court and District Courts of New York City. Its jurisdiction in all other counties was transferred to the County Court. When the Court of Common Pleas of the City of New York was abolished by the Constitution of 1894, it was the oldest judicial tribunal in the State of New York. Its jurisdiction was transferred to the New York Supreme Court.”

The Mayor’s Court was initially established in Hempstead Convention of 1665. The first English Governor of New York Richard Nicoll introduced a Charter for the City of New York “that placed the executive power of the City in the hands of a mayor, five aldermen and a sheriff, all of whom were appointed by the Governor. These officials, with the exception of the sheriff, also constituted the judges of the Mayor’s Court”.

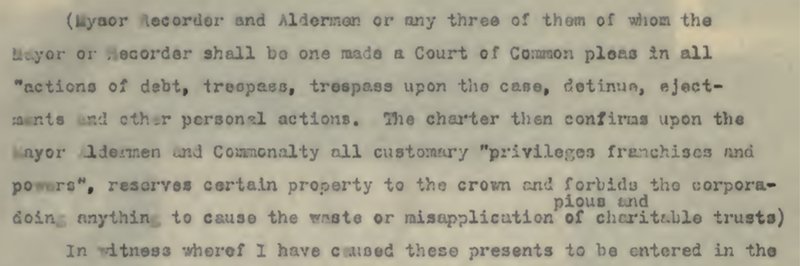

Formally known as the Court of Common Pleas, this judicial body was refined by 1686 by the Dongan Charter of the City of New York. This document, promulgated by the 5th Colonial Governor of New York Thomas Dongan, defined the Court as “Mayor, Recorder, and Alderman shall be a Court of Common Pleas in all actions of debt, trespass, trespass upon the case, detinue, ejectments and other personal actions. The Charter then confirms upon the Mayor, Alderman and Commonalty all customary privileges, franchises, and powers.”

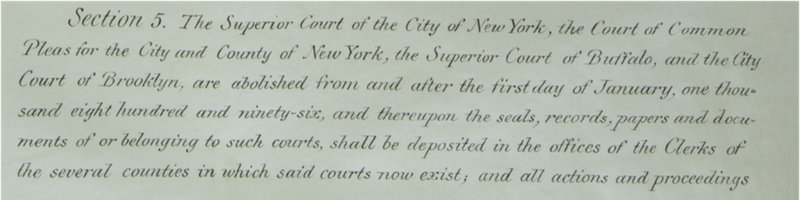

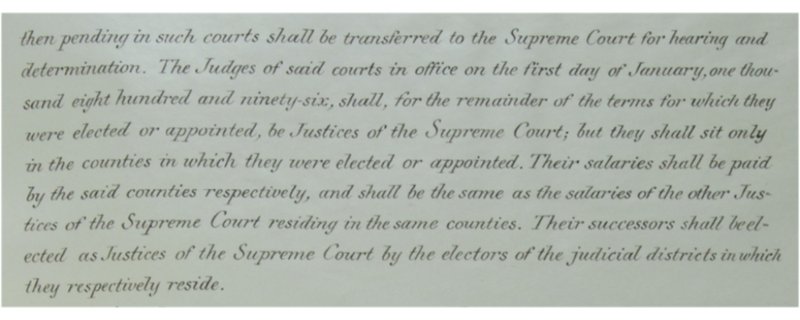

The Mayor’s Court endured in New York City until it was abolished during the 1894 Constitutional Convention which incorporated the court into the New York Supreme Court.

From Section 5 of the 1894 New York State Constitution:

the Court of Common Pleas for the City……are abolished from and after the first day of January, one thousand eight hundred and ninety-six

Notes

This bail document makes use of the “long s”, a typographic convention in use until the late-18th century. Depending on local custom, lower-case “s” characters would be written with the character “ſ” resembling a lower-case “f”. This can be seen in the word “Tuesday” written as “Tueſday”.

Historical Society of the New York Courts, Court of Common Pleas, 1686-1895, https://history.nycourts.gov/court/court-common-pleas/

Historical Society of the New York Courts, Richard Nicoll 1624-1672, https://history.nycourts.gov/figure/richard-nicoll/

Dongan Charter of the City of New York, 1686, Hathi Trust, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011715129

New York State Archives, Fourth Constitution of the State of New York, https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/collections/3518

An (incomplete) schedule and list of rules for the Probate Court of York County Maine. This broadside is divided into two sections. The upper section outlines the court schedule and location (Alfred, Limerick, Saco, Kennebunk, North Berwick, and York). The lower section is a list of 16 court rules, most of them procedural.

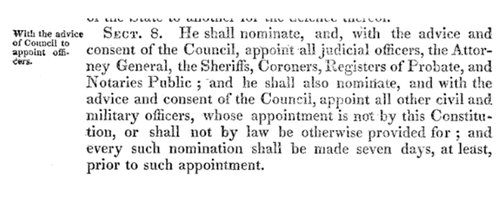

Maine’s system of county probate courts was established in the 1820 Constitution. In this original version, Officers of the Court were directly appointed by the Governor of Maine.

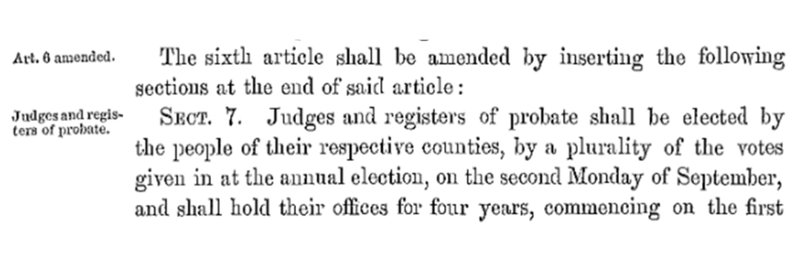

The appointment process of probate justices was altered by constitutional amendment in 1855. This successful amendment went into effect on February 28, 1856 and allowed for Judges and Registers of Probate to be elected by “the people of their respective counties” rather than gubernatorial appointment. This referendum question appeared on the ballot as:

Shall the Constitution be Amended as Proposed by a Resolve of the Legislature Providing that the Judges of Probate, Registers of Probate, Sheriffs and Municipal and Police Judges shall be Chosen by the People?

Constitution of Maine, 1820, Section 8: https://legislature.maine.gov/uploads/originals/const1820.pdf

Maine State Legislature, Amendments to the Maine Constitution, 1820 – Present, https://www.maine.gov/legis/lawlib/lldl/constitutionalamendments/

Acts and Resolves Passed by the 34th Legislature of the State of Maine, 1855, http://lldc.mainelegislature.org/Open/Laws/1855/1855_RES_c273.pdf