Officially founded in 1895, Pitt Law has prepared students to become excellent attorneys and leaders, consistently adapting to the changing landscape and needs of law and society. We invite you to read about the school's evolution, alums and faculty, and defining moments that have shaped Pitt Law into the institution it is today.

The founding of the School of Law at the University of Pittsburgh - at the time known as the Western University of Pennsylvania - is commonly attributed to the year 1895. Yet, graduates were emerging from the law department as early as 1847. Although several law schools were established in the early 19th century, until well past 1850 the primary method of legal education in the United States then was apprenticeship with an established lawyer, followed by the bar examination. Many lawyers did not have the benefit of such training, instead preparing themselves for the bar through self-directed reading. Thus, the law school was embarking on largely uncharted territory, finding itself at the forefront of university-based legal education when it established law classes in the fall of 1843, offering courses at just thirty-seven and one-half dollars a term, payable in advance.

Walter H. Lowrie was appointed the first law professorship, having previously taught rhetoric and belle-lettres, a form of instruction based on the analysis, appreciation, and creation of literature and literary works that were considered to be of high artistic value. Herman Dyer, dean of the faculty at the University, was responsible for the creation of this position and the law department as a whole, but died in the Great Fire of April 10, 1845 when the University's hall at Third Street and Cherry Way was destroyed, along with the entirety of its records. While the names of the students enrolled in these first law courses are lost, minutes from the Board of Trustees in 1847 indicate that the Bachelor of Laws degree was conferred upon four individuals: Robert Finney, James C. McKibben, Matthew Stewart, and Matthew B. Lowrie, whose relation to Professor Lowrie is unknown but assumed. These four men were the University's first law graduates.

Walter H. Lowrie was appointed the first law professorship, having previously taught rhetoric and belle-lettres, a form of instruction based on the analysis, appreciation, and creation of literature and literary works that were considered to be of high artistic value. Herman Dyer, dean of the faculty at the University, was responsible for the creation of this position and the law department as a whole, but died in the Great Fire of April 10, 1845 when the University's hall at Third Street and Cherry Way was destroyed, along with the entirety of its records. While the names of the students enrolled in these first law courses are lost, minutes from the Board of Trustees in 1847 indicate that the Bachelor of Laws degree was conferred upon four individuals: Robert Finney, James C. McKibben, Matthew Stewart, and Matthew B. Lowrie, whose relation to Professor Lowrie is unknown but assumed. These four men were the University's first law graduates.

Classes were then held in another university building on Duquesne Way, until that building coincidentally burned down in 1849, and continued in the basement of the Third Presbyterian Church until Professor Lowrie was elected to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania in 1951. Adding to this tumultuous period of bad luck, the onset of the Civil War later diverted the focus away from educating attorneys and toward efforts like manufacturing munitions for the Union Army, further disrupting the development of the School of Law.

In the midst of a brewing war, the vacant law professorship was not filled until 1862 by the Honorable Moses Hampton, President Judge of the District Court of Allegheny County. The following year, Henry Williams, Esquire succeeded him and delivered lectures in law. Williams later became a Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania in 1887.

By 1870, the University attempted to reinstitute formal legal education through the design of a two-year program, culminating in a Bachelor of Laws degree. To implement this proposal, the University hired three prominent lawyers to conduct the program: Hill Burgwin, Esquire, who lectured on the practice and pleadings of common law and real estate law; W.T. Haines, Esquire, who covered criminal law, domestic relations, insurance, commercial law, and Pennsylvania law; and William Bakewell, Esquire, who taught equity, jurisprudence and practice, constitutional law, patent law, contracts, corporations, and U.S. law.

However, by 1873, the program had collapsed once again, largely due to opposition from some of the city's lawyers, including a University trustee, who were against any system that would undermine the traditional system of "reading law" and legal apprenticeship. Additionally, faculty members were accused of managing the university's finances for personal gain, claiming that the trustees had no oversight over financial affairs and contenders feared graduates would receive special privileges regarding law practice admission.

Efforts to resolve this conflict failed, namely by Chancellor George Woods in the attempt to correct any wrong impressions that may have been made to reach an agreement, leading to the resignation of the professors and the abandonment of the law program in 1873.

By 1895, Pittsburgh was already heavily industrialized, a steel capital standing at the confluence of the Three Rivers. With a lengthy economic recession coming to a close in the hard times of 1893, a prosperous period of recovery was about to begin. The climate was favorable for Pittsburgh's industrialists, bankers, and, now, lawyers. Yet there was still no law school in the city, a circumstance that galled a small group of prominent Pittsburghers, among them William J. Holland, the Chancellor of the Western University of Pennsylvania.

Chancellor Holland, determined to establish a law school, successfully convinced the Allegheny County judges to appoint a committee to work with the trustees in establishing a law school as part of the University. In 1894, a curriculum committee had issued a report to the trustees, stating: "Pittsburgh is the only large city in the United States as yet without a law school. It is manifestly the function of a university to provide such a school." Nearly 30 years later, Chancellor Holland recalled his master strategy: "I went to my honored friend, John D. Shafer, unfolded my scheme, put the whole matter in his hands, and told him to go ahead, select his own faculty, and organize the school." With that, John D. Shafer became the founding genius behind the School of Law.

On October 14, 1895, the Department of Legal Instruction was established and classes were conducted in the orphans' court rooms in the old Allegheny County Courthouse. 35 students matriculated to the fledgling law school. Admission standards required the candidates to be at least 18 years old and of good moral character. If the applicant had a college degree or was a qualified teacher, admission was without examination. All others were admitted upon showing proficiency in history, mathematics, literature, and items of general knowledge. Tuition was $50 a term for degree students, plus a $5 matriculation fee, and $25 per term for non-degree students attending individual courses. Degree candidates had to prepare and submit a thesis to receive the Bachelor of Laws degree at the University's commencement. Special students received certificates of attendance for completed courses. The school used the Allegheny County Law Library, as it had no law library of its own.

On October 14, 1895, the Department of Legal Instruction was established and classes were conducted in the orphans' court rooms in the old Allegheny County Courthouse. 35 students matriculated to the fledgling law school. Admission standards required the candidates to be at least 18 years old and of good moral character. If the applicant had a college degree or was a qualified teacher, admission was without examination. All others were admitted upon showing proficiency in history, mathematics, literature, and items of general knowledge. Tuition was $50 a term for degree students, plus a $5 matriculation fee, and $25 per term for non-degree students attending individual courses. Degree candidates had to prepare and submit a thesis to receive the Bachelor of Laws degree at the University's commencement. Special students received certificates of attendance for completed courses. The school used the Allegheny County Law Library, as it had no law library of its own.

The following was the prescribed course of study for the fall of 1896:

The men Dean Shafer hired for the initial faculty, including Samuel Mehard, Thomas Herriott, Clarence Burleigh, James C. Cray, William McClung, Thomas Patterson, and William Warson Smith, were all active practitioners who would teach part-time in the afternoon, usually from 1 to 5 p.m. This was not only customary but was regarded as wise by those who were used to the old preceptoral system.

The first class, graduating in 1897, consisted of college graduates and sons of prominent members of the bench and bar. That same year, the school moved to bigger quarters in the old Pittsburgh Academy Building, occupying two rooms at the southwest corner of Ross and Diamond Streets, and stayed there until the First World War.

With the move to larger quarters, a moot court program was instituted for second and third-year students who met once a week for instruction in Advocacy. Also quite early on, a fellowship was established to provide carefully selected graduates with an additional year for each to "perform such duties as are assigned to him by the faculty, receiving for his services the sum of $250."

In 1900, the School of Law joined with 31 other law schools to found the Association of American Law Schools, of which it remains a charter member.

On July 11, 1908, the Western University of Pennsylvania changed its name to the University of Pittsburgh, purchasing the present campus in Oakland at that time. The Law Department officially became the Pittsburgh Law School.

A committee was appointed to negotiate with the County Commissioners regarding the continuation of law school operations in the County building at the corner of Ross and Diamond Streets. In case of failure to obtain the Commissioners' consent, the committee was to seek permission from the Orphans' Court judges to temporarily use the Orphans' Court rooms.

The County Commissioners granted permission for the law school to occupy the old University building at the corner of Ross and Diamond Streets until the building was demolished. The Law School was assured of thirty days' notice to vacate. A year later, Judge Shafer was authorized to find a new location for the law school, which led to another move to the Chamber of Commerce Building at Seventh Avenue and Smithfield Street in 1919.

At the turn of the century, societal shifts and evolving perspectives necessitated significant changes within the law school. As the legal landscape adapted to new social realities, the school sought ways to keep up with the modern times.

While there were no female students in the school at this early period, the school presented a series of four lectures covering property rights of women, women’s legal status, investments, and the “Sociologiscal and Economical Opportunities for Women”. The program included an interesting bibliography listing magazine articles such as Susan B. Anthony’s “Woman’s Half-Century of Evolution” and G.G. Corks “The Law’s Partiality to Married Women”.

However, it would not be long until the school began to welcome inclusivity and diversity.

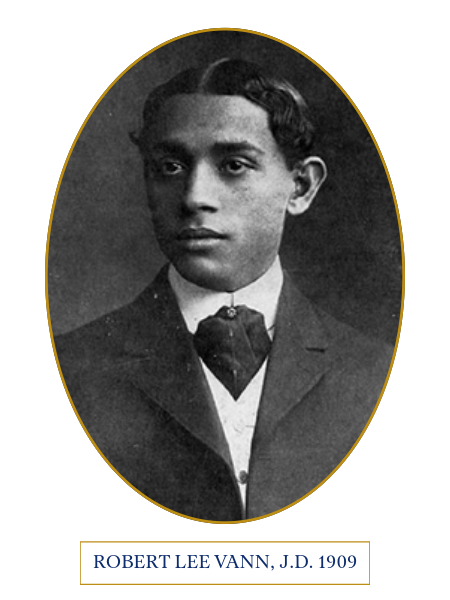

Robert Lee Vann made history as the first Black graduate of the law school in 1909 , also serving as the first Black editor of the student newspaper at the University of Pittsburgh, The Courant. Born in 1879 in North Carolina, he began his education at Waters Training School, graduating as valedictorian in 1901. He later attended Wayland Academy, Virginia Union University, and received a scholarship to Western University of Pennsylvania, where he earned both his undergraduate and law degrees. To finance his education, he worked in a railroad dining car from Pittsburgh to Connellsville, serving dinner in the evening and breakfast on the return trip the next morning. After passing the bar exam in 1909, Vann became one of only five Black attorneys in Pittsburgh, opening his own law practice the following year.

Robert Lee Vann made history as the first Black graduate of the law school in 1909 , also serving as the first Black editor of the student newspaper at the University of Pittsburgh, The Courant. Born in 1879 in North Carolina, he began his education at Waters Training School, graduating as valedictorian in 1901. He later attended Wayland Academy, Virginia Union University, and received a scholarship to Western University of Pennsylvania, where he earned both his undergraduate and law degrees. To finance his education, he worked in a railroad dining car from Pittsburgh to Connellsville, serving dinner in the evening and breakfast on the return trip the next morning. After passing the bar exam in 1909, Vann became one of only five Black attorneys in Pittsburgh, opening his own law practice the following year.

In 1910, Vann became the legal counsel for The Pittsburgh Courier, eventually rising to become the paper's editor, treasurer, and publisher. Under his leadership, the Courier became the most influential Black newspaper in the country, with a circulation of 250,000 in the 1930s and nearly 400,000 by 1947. Vann used the paper's editorial pages to advocate for social and political reforms, making him a political force throughout the nation. He served as the fourth assistant city solicitor in Pittsburgh from 1917 to 1921, the highest position held by an African American in the city government at that time.

Vann retired in 1936, leaving behind a successful legal practice and a legacy of social justice and civil rights advocacy. His life serves as a testament to the power of education and influence for change, inspiring generations to strive for Black empowerment, excellence, and equity.

To learn more about Robert Lee Vann, check out his Alumni Highlight, part of our Breaking Barriers: Milestones in Diversity at Pitt Law Exhibit.

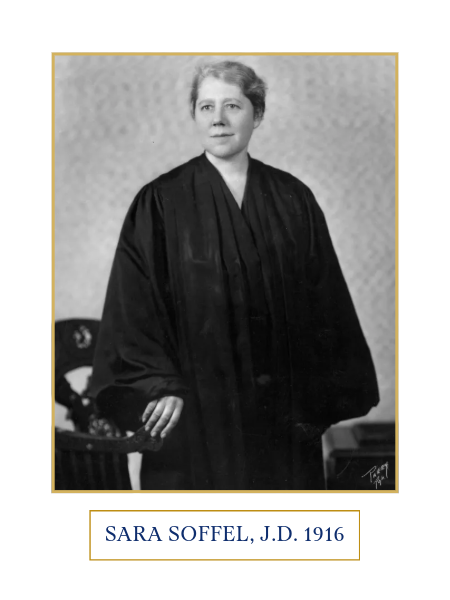

Seven years later, the school would experience yet another first. The graduation in 1916 marked a significant milestone for the law school, as Sara Mathilde Soffel, along with Marie Grace Clark Gallagher and Lily Virginia Pickersgill became the first three women to successfully complete their legal studies. Notably, Soffel was the sole individual among them to complete the entire course of study at the law school, making her the first woman to undergo her legal studies entirely at the University of Pittsburgh. She graduated as the top student in her class, earning her a cash prize and a teaching fellowship for one year.

Soffel later distinguished herself by being the first woman elected to a judgeship in Pennsylvania when she was elected a Judge of the Court of Common Pleas of Allegheny County from 1942-1962. In 1939, she was the first woman to run for the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. Despite her running on both major parties' tickets and garnering 742,000 votes statewide with 300,000 more votes than the Democratic runner-up and 28,000 greater than the Republican runner-up, both the Democratic and the Republican party establishments refused her the nomination.

To learn more about Judge Sara Soffel, check out her Alumni Highlight, part of our Breaking Barriers: Milestones in Diversity at Pitt Law Exhibit.

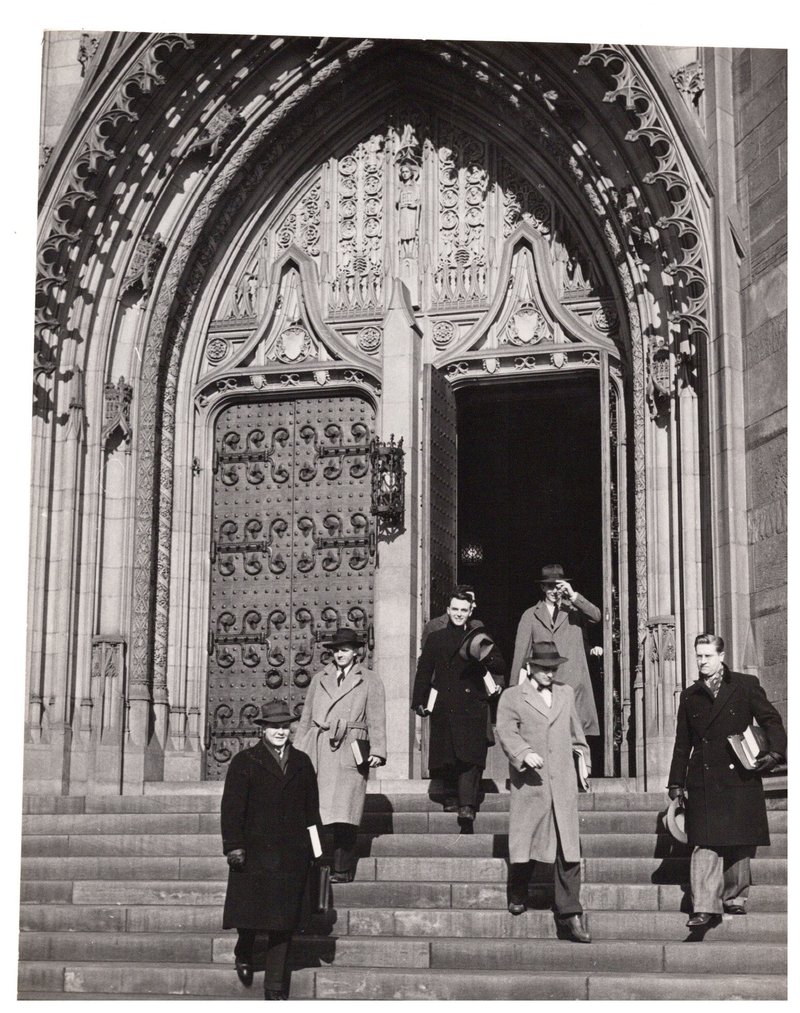

After the St. Patrick's Day flood of 1936 that left most of downtown Pittsburgh, the school's quarters in the Chamber of Commerce Building were left uninhabitable. That spring, the School of Law relocated to higher ground on the Oakland campus, becoming the first school to fully occupy the Cathedral of Learning on its 13th, 14th, and 15th floors. However, this move presented several challenges.

To start, the Cathedral of Learning was still under construction.

Second, the move from downtown meant the end of an era of convenience. In fact, the move wasn't heralded with overwhelming approval from either students and faculty. Faculty opposed the move due to the difficulty of commuting from their downtown offices to Oakland for afternoon classes. On the other hand, students who commuted by train were also inconvenienced, as the line terminated at Union Station. For many students, the biggest expense became carfare, adding to the challenge of getting to school.

In the 1940s, the onset of World War II called many men to service, resulting in disruptions to the traditional academic year. By the 50s, the school seemed to already be outgrowing the space, hampering the program. Many students utilized their G.I. Bill benefits to fund their studies, and new policies welcomed a larger faculty, manning the curriculum now with full-time faculty members versus the previous part-time attorneys. With this growth, it became increasingly clear that a new building was necessary.

In the school's earliest years, students used the library in the courthouse. In 1915, the school began building its own library with an initial collection of 200 law books donated by the faculty. Around the same time, the trustees of the University provided a lump sum of $5,000 to purchase 5,000 books—an optimistic order even at the deflated prices of the time. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the library continued to expand, supplemented by donations of private collections. By the time of the move to the Cathedral of Learning, the school boasted a library of 23,000 volumes, a vast difference from its original collection of 200. The number of books consistently outpaced the available space. From the 1960s onward, large numbers of volumes had to be removed from the open stacks and placed in hard-to-reach storage areas. Worse yet, the lack of space meant that needed acquisitions had to diminish.

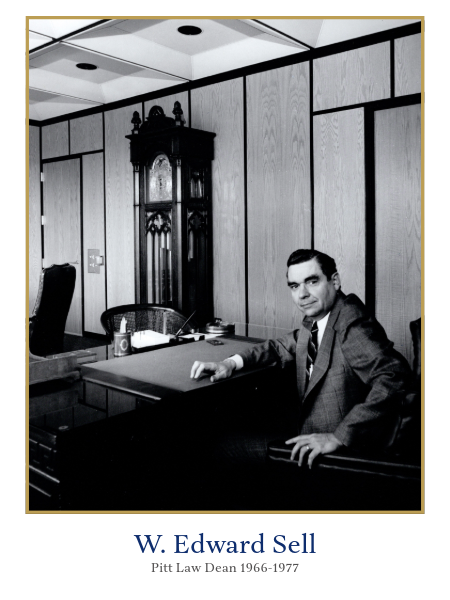

The size of the student population grew as well. During the deanship of W. Edward Sell, the School of Law's enrollment increased from barely 100 students in 1965 to more than 500 in 1975. There were three main reasons for this growth. The University's state-related status, earned in 1967, provided state residents with a tuition subsidy that boosted enrollments. Additionally, the romanticizing of the legal profession—viewing lawyers as activists against corruption and agents of constructive change—attracted students who might have otherwise pursued degrees in political science, economics, sociology, and similar fields. The women's rights movement also played a role, encouraging women to seek entry into formerly male-dominated professions.

To learn more about Pitt Law in the Cathedral of Learning, check out the Law in the Cathedral Photograph Collection, part of our Archives and Special Collections Digital Exhibits.

Faced with the prospect of ever-increasing enrollment and severe space shortages, Dean Sell, with the aid of some staunch alumni and a sympathetic University administration, lobbied relentlessly for a new building. After a number of false starts, ground for the new structure was broken in November 1972, and three more years were to pass before the building was completed.

Leaving behind its 40-year residency in the Cathedral of Learning, the spring semester of 1976 marked the beginning of a new era, as classes commenced in the new Law Building on the corner of Forbes and Bouquet. The site was previously home to Forbes Field, where both the Pittsburgh Pirates and Steelers once played. In its place stands the Barco Law Building, known then simply as the School of Law Building, the first facility built specifically for legal education at the University of Pittsburgh, aspiring to set a standard of utility and beauty for law schools everywhere. It stands as a testament to years of dedication and effort by a committed group of individuals, representing the culmination of support from countless alumni who have generously contributed their time and resources to enhance the school.

To explore pictures of the Barco Law Building, check out the Barco Law Building Highlight, part of our Archives and Special Collections Digital Exhibits.

In October of 1976, Dean W. Edward Sell announced his resignation, effective before the 1977-78 academic year. His tenure had been marked by significant achievements, including the construction of the new building, expansion of the faculty and student body, and strengthening of the Law Alumni Association. Sell's departure set the stage for a new leadership era at the law school, as he had achieved his major goals and sought to ensure a smooth transition for his successor.

In the summer of 1977, Professor John E. Murray, Jr. assumed the role of Dean of the School of Law. His appointment marked a significant transition for the institution. Dean Murray, who had served as Associate Dean for Academic Affairs for eight years, brought with him a wealth of experience and a strong academic background. He completed his Bachelor of Arts at LaSalle University, his Juris Doctor at Catholic University, and his Doctor of the Science of Jurisprudence at the University of Wisconsin. Prior to joining our faculty, he had a notable tenure at Duquesne University School of Law where he held various positions, including Acting Dean, and earned recognition for his scholarly contributions. Murray resigned at the end of the 1983-84 academic year, citing disagreements over the law school budget.

On April 23, 1984, Chancellor Wesley Posvar and Provost Roger Benjamin announced the appointment of Richard J. Pierce as the new dean of the School of Law. Dean Pierce, previously W.R. Irby Professor of Law at Tulane Law School, brought a wealth of experience in energy law and administrative roles. His appointment was seen as a strategic move to guide the school through a new planning phase.

His departure stemmed from unresolved funding disagreements with the University administration. As he prepared to leave, Pierce expressed his dissatisfaction with the University’s funding decisions and affirmed his belief in the School’s strong support network. He acknowledged Mark A. Nordenberg, the Associate Dean, as the interim leader and voiced confidence in his ability to guide the School through this transitional period.

To learn more about the deans of Pitt Law, visit our ASC website, where you can find detailed profiles and information about their backgrounds, initiatives, and contributions to the school.

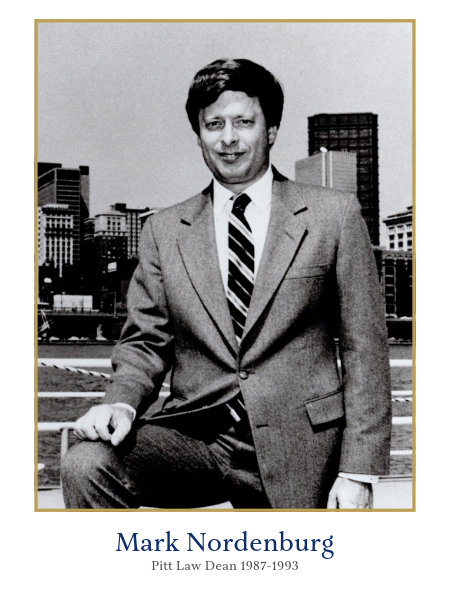

Dean Pierce’s resignation led to Mark Nordenberg’s appointment as Acting Dean. Nordenberg, previously recognized for his excellence in teaching and administrative service, stepped into this role while a national search for a permanent dean was conducted. Following his interim period, Nordenberg was formally appointed Dean of the School in May 1987.

Dean Pierce’s resignation led to Mark Nordenberg’s appointment as Acting Dean. Nordenberg, previously recognized for his excellence in teaching and administrative service, stepped into this role while a national search for a permanent dean was conducted. Following his interim period, Nordenberg was formally appointed Dean of the School in May 1987.

During his tenure, Dean Nordenberg faced the critical task of rebuilding relationships with the University administration and alumni. One of his early accomplishments was securing increased funding for the law library, establishing a development office, upgrading the placement office, expanding faculty and staff, and creating new tuition-remission scholarships for non-resident students. His efforts were supported by University officials including Provost Dr. Donald Henderson and Vice Provost Dr. Jack Daniel.

These initiatives led to a significant improvement in the law school’s standing within the University. By the mid-point of Dean Nordenberg’s administration, the Provost and Chancellor publicly recognized the School of Law as "one of the jewels in the University crown," reflecting a more supportive and collaborative relationship between the law school and the broader University community.

Under Dean Nordenberg’s leadership, substantial efforts were devoted to fortifying connections between the School of Law and its alumni, as well as enhancing relationships with the broader legal profession. Dean Nordenberg's extensive professional involvement, including his service on the United States Advisory Committee on Civil Rules and the Pennsylvania Civil Procedural Rules Committee, provided a strong foundation for these initiatives. His active participation in the school’s trial advocacy programs also earned him considerable respect within the legal community.

In the fall of 1987, George J. Barco, '34, and his daughter Yolanda G. Barco, '49, made a landmark $1 million donation to the library, the largest gift in the school’s history. This endowment aimed to enhance the library’s resources and support the school’s teaching and research missions. Following George Barco’s death, additional contributions increased the total gift to approximately $2 million.

To learn more about Yolanda Barco, check out her Alumni Highlight, part of our Breaking Barriers: Celebrating Diversity at Pitt Law Digital Exhibit.